Cupid & Psyche & the Mother-in-Law From Hell

Mamacita says: I’ve been blogging for over sixteen years, and every Valentine’s Day, I like to re-tell the story of Cupid and Psyche to the Blogosphere.

Mamacita says: I’ve been blogging for over sixteen years, and every Valentine’s Day, I like to re-tell the story of Cupid and Psyche to the Blogosphere.

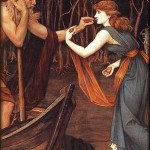

Why? Because it’s one of my favorite myths. I love this story. I’d post more pictures about it, but everybody’s nekkid.

Mamacita says: It’s Valentine’s Day, and since many people associate this day with Cupid, let’s talk for a moment about the REAL Cupid. Well, the real mythological Cupid.

Cupid is not a fat naked baby, flying around shooting arrows into people to make them fall in love with the first living thing they see, causing people to have inappropriate relationships with cows and bulls and goats. It was used as an excuse by some people, but we won’t go there.

It’s kind of along the same lines as the alcoholics who tried to rationalize their choices by swearing they were just worshipping Bacchus/Dionysus, and the knocked-up teenagers who swore they were abducted by Zeus. . . .

Ahem.

In some myths, Cupid/Eros IS a perpetual child, but in most of the myths, he is as all the other gods (except Hephaestus) were: indescribably beautiful. Unfortunately, his mother was the goddess Aphrodite/Venus, and even though she was the goddess of love and beauty, she was a BITCH.

Here is the story of what happened when Cupid dared to fall in love and try to have a life of his own. Heh, and some of you think YOU have mother-in-law problems. . . .

==

Once upon a time – was there EVER a better way to begin a story? – there was a King who had three daughters, all beautiful, and the youngest daughter was the most beautiful of all. In fact, and this was dangerous talk in any myth, people said that this young princess was more beautiful even than the goddess of beauty herself. Now, whenever, in a myth, people compare a mortal to a god or goddess, you will know in advance that the poor mortal, even though he/she probably did nothing wrong, is going down. DOWN. Circling the drain down.

This young princess, whose name was Psyche, begged the populace not to say such things, but people were heedless and full of gossip even back in these days, and the talk went on and on. Eventually, of course, Aphrodite heard of it, and she was FURIOUS.

She called her son Cupid to her, and instructed him to fly down to earth and shoot an arrow into Psyche, making sure the first living thing she saw would be a monster that would devour her even as she could not help falling in love with it.

What Aphrodite had not foreseen was this: Cupid took one look at Psyche, was dazzled by her beauty, tripped and fell on one of his own arrows and fell in love with her himself. It was the real thing, too; it would have happened with or without magic love arrows or anything else. He saw her, and he loved her.

He knew, though, that he would have to keep it a secret from everyone, especially his jealous, possessive mother. Therefore, he would have to somehow get Psyche away from her family and sneak her to his palace.

He sent Psyche’s father, the King, a dream that directed him to go to an Oracle – a fortuneteller – who told him that he must take his beloved daughter to the top of the mountain and let a Demon take her to wife.

The King did not dare to disobey, so he and Psyche’s sisters walked with Psyche up the mountain and left her on a jutting rock to await her demonic husband. She did not understand what was happening, and could not think why she should be treated so, but back in the days of the myths, people did what the gods told them to do and chalked it all off to the Fates.

That night, the West Wind swooped down and flew with her to her new husband’s home. She tried to ask Zephyrus what was to become of her, but he would not, or could not, answer. He, too, was following orders.

To Psyche’s surprise, Zephyrus took her to a beautiful palace, even more beautiful than her father’s palace back home. Invisible servants waited on her hand and foot. Delicious food was served to her, three times a day. Lovely clothing appeared in her closet.

She dreaded the night, because she knew that her new husband would come to her in the marriage bed, but when he came into the room, she knew no fear. She could not see him in the dark, but he told her he loved her and would always love her. He also told her that she must NEVER see him in the light.

She dreaded the night, because she knew that her new husband would come to her in the marriage bed, but when he came into the room, she knew no fear. She could not see him in the dark, but he told her he loved her and would always love her. He also told her that she must NEVER see him in the light.

He came to her every night after dark, but was gone before the morning light fell upon his face. Psyche knew that she loved him, but she did not even know his name.

Then, she got homesick.

After much crying and begging from his wife, Cupid told her that her two sisters would be allowed to visit her. Psyche was happy to hear this, for living alone in a huge castle with only invisible servants by day and a nameless, faceless husband by night was hard on a girl. Besides, she was pregnant.

Cupid was happy to hear this news, but he warned his wife that as long as she never looked upon her husband’s face, the baby would be immortal, but if she could not resist temptation and saw him in the light, the baby would be mortal and eventually die.

By this time, Psyche loved her husband so much she would have done anything for him. She agreed.

When her sisters arrived, they were impressed with the richness and luxury their sister enjoyed, but their jealousy of her good fortune overcame their love for her. They were amazed that Psyche was pregnant with the child of a husband she had never seen and didn’t even know by name. They told Psyche that he must be a hideous monster, and that she had a right to see her husband’s face. They told her that if he was indeed a monster, she would have to kill him. They told her these things over and over until they convinced her that it would be the only right thing to do. After all, why should a wife not know her husband’s face and name? It was so logical!

That night, after her husband had come to her and then fallen asleep, Psyche fetched an oil lamp and a knife. The lamp would show her his face, and if he was indeed a monster, she would kill him with the knife.

But she trembled, and a drop of hot oil fell on him. He awoke, and turned to look at  her. She saw, in the light, not a hideous creature from the depths of hell itself, but a beautiful young man with golden wings, looking at her with love and pain and despair. He got out of bed and flew away, and Psyche knew she would never see him again.

her. She saw, in the light, not a hideous creature from the depths of hell itself, but a beautiful young man with golden wings, looking at her with love and pain and despair. He got out of bed and flew away, and Psyche knew she would never see him again.

Psyche blamed herself for losing her husband. Because of her curiosity and disobedience, she was alone, and pregnant. She prayed desperately to the gods, but they did not answer, and Cupid did not return to her.

She decided to go to Aphrodite, Cupid’s mother, and offer her services as a servant, hoping that Cupid might admire her devotion and return to her.

What naive Psyche didn’t know was that her mother-in-law didn’t merely dislike her; she HATED her, and was eager to do great harm to her to keep her son away from his wife. She was still angry because the townspeople in Psyche’s homeland had remarked that Psyche was more beautiful than Aphrodite, and the fact that this girl was now pregnant with her son’s child made Aphrodite even more furious. Aphrodite was determined to punish Psyche for taking some of her son’s affection from his mother.

Aphrodite set Psyche to work on a series of ridiculous, impossible tasks. She had to sort a roomful of different grains by nightfall; had it not been for the ants, who helped her sort the grains into various piles, she could never have finished. Next, Aphrodite told Psyche she had to shear the wool from a flock of deadly, possessed sheep that were hypnotized, so that they tried to kill all who came near. Fortunately, the reeds along the riverbank advised Psyche that she could get enough wool from the thorny bushes the sheep had passed through, instead of trying to deal with these evil sheep.

Each time Psyche succeeded, Aphrodite became angrier and more determined to break her. The tasks became more and more difficult. She sent Psyche to fetch water from the river Styx, the river of death, but fortunately, Zeus took pity on Psyche and sent one of his mighty eagles to fetch the water for her.

Finally, Aphrodite told Psyche to enter the Underworld and fetch her box of cosmetics from Persephone, Queen of the Underworld. No mortal had ever entered the World of the Dead and returned. The night before this task, she lay in her bed and wept.

Finally, Aphrodite told Psyche to enter the Underworld and fetch her box of cosmetics from Persephone, Queen of the Underworld. No mortal had ever entered the World of the Dead and returned. The night before this task, she lay in her bed and wept.

Suddenly, she heard a voice, telling her how to succeed in this task, and also warning her not to open the box once she got it in her hands. This piqued Psyche’s curiosity.

In a myth, whenever someone is extremely curious about something, there’s going to be trouble.

Psyche entered the Underworld. She crossed the Styx, paying Charon his toll. (This is why, in many cultures even today, the dead are buried with a coin on each eyelid.)  She gave food to Cerberus, (now you know where the idea of Hagrid’s “Fluffy” came from!) to distract him so she could run through the gate of Hades without being devoured. (Meat is placed in the hands of the dead, and when rigor mortis set in, the meat was secure in the fist.) Psyche did as the voice had instructed her throughout her entire visit, and finally, box in hand, she returned to the world of the living.

She gave food to Cerberus, (now you know where the idea of Hagrid’s “Fluffy” came from!) to distract him so she could run through the gate of Hades without being devoured. (Meat is placed in the hands of the dead, and when rigor mortis set in, the meat was secure in the fist.) Psyche did as the voice had instructed her throughout her entire visit, and finally, box in hand, she returned to the world of the living.

Once she got back to her palace and was alone with this mysterious box, Psyche’s curiosity got the better of her. What harm could one little peek do? She wasn’t going to TOUCH anything in there, after all. But when she opened the box, she fell into a deep slumber.

By this time, Cupid’s anger had passed, and he longed for his wife and baby. His mother tried her best to dissuade him, but for the first time in his life he defied her openly and, in spite of her magical attempts to hold him, flew out of his childhood home and went back to the castle he had built for his own family.

He found his wife, sound asleep on the floor of her room, and so deep was her sleep that Cupid thought she was dead, and wept as he held her in his arms. He bent to her for one last kiss, and she awakened!

Cupid and Psyche were together at last, in the light, and both liked what they saw.

However, there was still the danger of Aphrodite, who still hated Psyche and who wanted her son Cupid’s full devotion. Cupid finally appealed to Zeus, King of the Gods, and asked him to make his wife immortal, that Aphrodite could no longer harm her, and Zeus agreed.

Cupid and Psyche lived happily ever after, and their daughter Volupta. . . well, that’s a whole other story, isn’t it.

==

I hope you saw the roots of a lot of fairy tales and other stories. The ancient myths are a treasure trove of literary points of origin. I also hope you noticed a lot of root words; the English language is a patchwork quilt of languages: we steal from everybody.

Mythology is one of my thangs. Can you tell?

Happy Valentine’s Day, all.

Somebody else can tell the story of St. Valentine. I like Cupid and Psyche.

This myth is also ONE of the origins of the expression “Opposites attract.”

Because Love is all emotional, see, and the Mind is logical, and. . . . oh, you know. And how ironic is it that the Ancients saw the male as the emotional one and the female as the logical one?

Mythology is so cool.

The Real Heroes Are the Unsung Heroes

Mamacita says: Is there anyone else out there who can flip through a history book and wonder where everybody is?

So many unsung heroes. Too many.

Far too many genuinely important people get no mention whatsoever, or maybe just a brief mention, in passing. So many people who really ain’t all that get whole chapters dedicated to them; don’t even get me started on General Custer – the man was a complete and total loser.

But. . . where is Madame Walker? Where’s Denmark Vesey? Clara Barton? Laura Bridgeman? Maria Mitchell? Amelia Bloomer? (Guess what got named after her?) Where is Elizabeth Blackwell? Marie Curie? Ira Hayes? Thomas H. Perkins? Joseph Lister? Louis Pasteur? Yuri Gagarin? Frances Willard? Lucy Stone? Sojourner Truth? Nikola Tesla? Miep Gies? King Haakon VII of Norway? Laika? And so many more. . . .

Our children don’t know who these people are. Some of their parents don’t, either.

Most of the time, in any kind of drama, the most important participants are not the ones in the limelight. The most important participants are standing in the wings, or behind the curtains, actually DOING something. They understand that it’s the “DOING something” that’s important, not the”being seen in the vicinity of people who are doing something”.

These people are did things, awesome things, things that helped shape our lives today. Inspiring things. Brave things. But how many of you actually know who they were and what it was they did?

Erma Bombeck was right spot-on: “Don’t confuse fame with success. Madonna is one; Helen Keller is the other.

IT: The pronoun of desire and hanging out

College friends shaving-cream-bombed by the men’s dorm. We knew what “it” was, and we knew we had it.

Mamacita says: I wonder sometimes if one of the reasons some people age horribly and die, is because they have stopped hanging out with friends.

Of course, if they are REALLY old, they may have stopped hanging out with friends because there’s not that much to do in the cemetery.

But for people (naming no names) who are perhaps just beginning to be on the old side, whose friends are still (mostly) alive, it’s just as much fun to hang out with friends as it was years ago, when we all skipped last hour Chemistry to pile into someone’s blue Corvair and head out to the State Park to meet guys.

When my children were little, and it was purt nigh impossible to get away and hang out with friends (partly because it was purt nigh impossible to get away, and partly because they had small children also; living a hundred or a thousand miles away contributed to the level of difficulty. . . .) those few and far-between episodes of getting together quite possibly saved what little sanity I do have.

When we meet now, and yes, Virginia, we still meet once in a while, though not nearly often enough, the only thing that’s really changed, besides our faces, hair, bodies, and big purses, is the fact that we no longer have little children at home. Some of us have GRANDCHILDREN. Not me, though.

Ahem. Are my children reading this journal?

But the giggles, the nonsense, the silliness, the goofiness, the sheer love and devotion, are all still there in full force; possibly in fuller force than when we were younger.

Yes, definitely. Fuller force.

Maybe because, THEN, we knew what we had but didn’t fully understand that it could vanish in the wink of an eye. We were young, we were attractive, we knew it. And it would last forever. How could it not? And NOW, we know what we had and we know what we still have and we understand completely that yes, it could very well vanish in the wink of an eye, and that yes, some of it already has. We have mirrors. And even though we no longer have some of ‘it,’ we also know that, whatever ‘it’ was, we still have SOME of ‘it.’ And we aren’t afraid to use it, either.

No, not THAT kind of ‘it.’ Although, now that you mention ‘it’. . . . . . . . . . .

Those of you with small children: be sure you make time for your friends. “Hanging out” isn’t just for teenagers. You need it more than they do. Hire one of them, and go meet your friends for a few hours. Keep doing it until you are dead.

Your older children and possibly a husband who won’t be requiring any sex for a while, might make a comment about how “hanging out” means something entirely different on an older woman with, um, body image deficiency. Remind them all that they know where the food is kept, and that the sofa sleeps one person very comfortably indeed. And then leave.

Get out there and use ‘it.’

Readers may interpret “it” as they please. All answers are probably correct.